blaugezeichnet.2024-09-13-08-28-56.jpg)

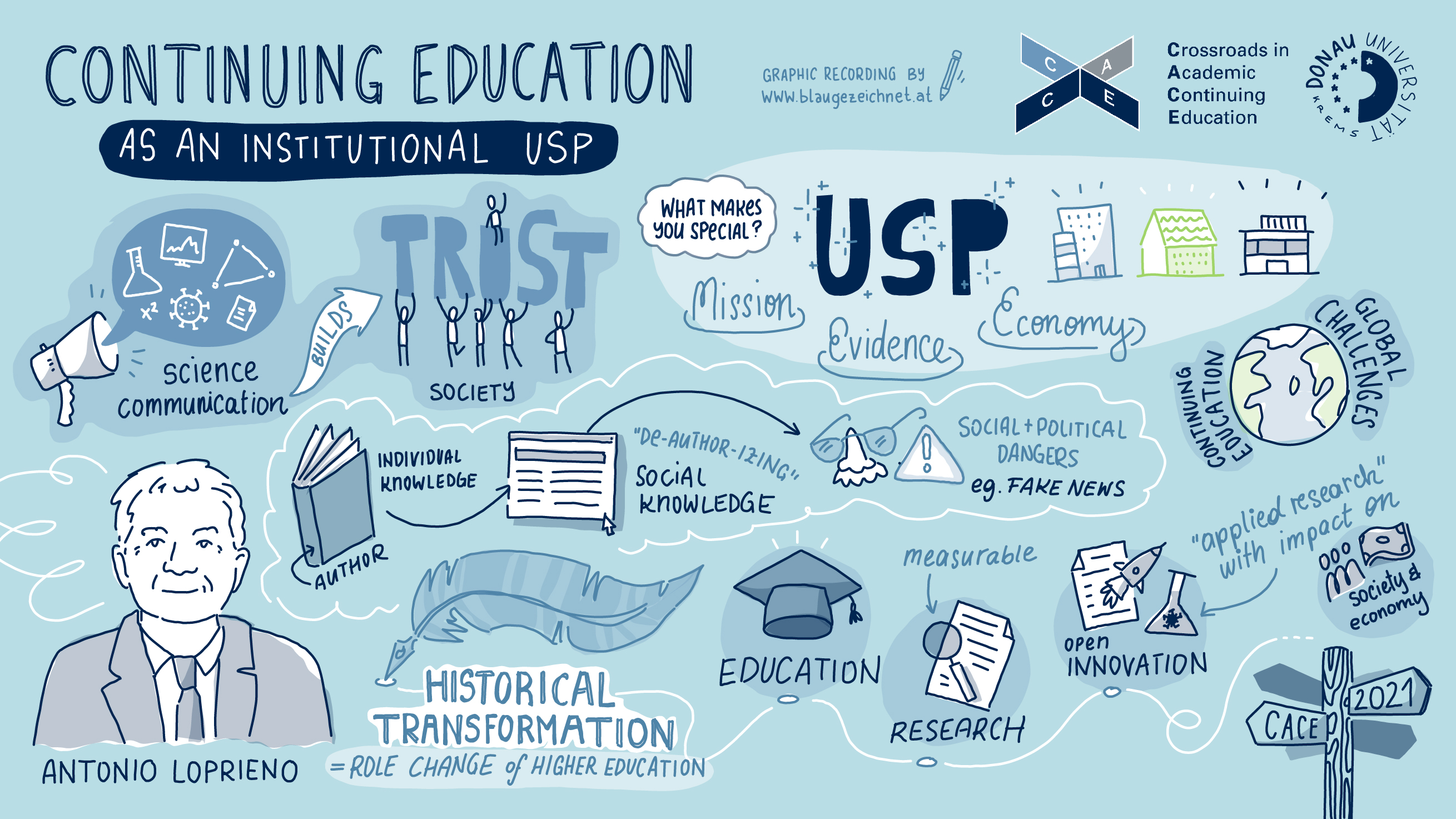

In the past, universities used to regard continuing education as a topic of lesser importance. Now, however, they are paying more and more attention to it. In his keynote, the former President of the University of Basel and current President of the Austrian Science Council, Antonio Loprieno, addressed the role of continuing education as a USP for academic institutions and explained its benefits for society as a whole.

He started out by taking the audience on a historical journey, tracing the development of European universities since the 19th century. Back then, three higher education models evolved: The “Humboldt model”, which is predominant in Central Europe and centred around science and research. The “Newman model”, which is typical of Anglo-Saxon countries and offers wider access to education; only after having acquired a certain level of general education do students specialise in particular scientific or professional fields. The “French model”, as applied by France’s “grandes écoles”, focuses on training students for their later professions.

In the 1990s the system started to change, and a major transformation of higher education took place, both in Europe and in other parts of the world. This transformation was driven by the Bologna Reform, which paved the way for several changes. From then on, universities became autonomous organisations and started to make their own decisions, for example concerning their study programmes. They also started to attach greater importance to their brand value and marketing so that they would stand out from the field. Increasing focus was also placed on the relevance of their work for society. So, instead of allowing them to focus on their core competences of teaching and research, academic institutions were now expected to conduct research with and on behalf of society, the so-called “third mission” of universities.

New forms of academic education evolved: In the UK, polytechnics were turned into universities. In Austria, Germany and Switzerland, universities of applied sciences emerged. In the course of the Bologna Process that started in 1999, the focus of university curricula was shifted to cater increasingly to the needs of labour markets. As of 2005, research replaced teaching and education as the most important task of academic institutions for the simple reason that research is easier to measure and track for sponsors and stakeholders. Since 2015 innovation has been all the rage, and universities have been expected to devote their work to the service of society. Due to this focus on providing benefits for society, applied research and university-level continuing education have become more important. Academic institutions have become part of the ecosystem they are also intended to benefit.

This explains why continuing education is playing an ever more important role, for example, when it comes to equipping students with entrepreneurial skills. Universities with a focus on continuing education are able to contribute significantly to innovation, as they combine an applied approach with an academic foundation and interact with students who bring practical questions from their professional lives into the universities. Transdisciplinary research approaches, as applied by the University for Continuing Education Krems, allow external stakeholders to get involved in academic institutions, opening up new fields of action in relation to current challenges such as climate change.

The heterogeneity of students enrolled in continuing education programmes also brings universities offering such programmes closer to the public, for example within the framework of collaboration projects between science and society. Such collaborative approaches allow wider circles of people to get involved; they also come with risks, though, as illustrated by the example of Wikipedia: if it is not clear who is the author of a text, there is a higher risk of fake news getting published or, at least, of „facts“ not being backed up by sufficient scientific evidence. Loprieno urged that uncontrolled developments of this kind had to be restrained and brought under control. He underlined the importance of communication in science and research, even though it is not always possible to make clear statements in science–something that resulted in a veritable communication challenge during the pandemic.